Epilepsy is a significant health problem. It can affect both physical and mental illness and there are concerns that it can impact patients of all ages, society and the country.1-3 Patients with epilepsy (PWEs) may have a seizure while working, which can lead to accidents that may adversely 4 affect employability. A systematic review study showed the employment rate of people with uncontrolled seizures to be about 58%, where employment is one of the psychosocial parts that significantly affects quality of life (QOL), symptoms such as low self-confidence and anxiety are also commonly

QOL.7-9 In addition, epilepsy could potentially affect their families, and caregivers.2,10 Previous studies have reported about the psychological status of PWE caregivers, where they experienced 31.30% anxiety and 33.59% depression which significantly impacted their QOL.11

According to a report by the WHO, around 50 million of the world’s population have epilepsy.12 Thailand has reported the prevalence of epilepsy many times. Among the 65 million people that make up the Thai population, 3.8-4.7 hundred thousand cases have been diagnosed with epilepsy.13

For up to 50% of the cases, the cause of the disease has been largely unclear. Many underlying diseases can lead to epilepsy, such as head injury, brain tumor, stroke, and brain infection.12 Many PWEs have found it challenging to control the seizures or the seizure medications affected their QOL.13

Previous studies have shown that seizures can affect the functioning of the brain and impact the patient’s daily life, including embarrassment after a seizure and lack of self- confidence. Compared to the general population, PWEs have a high unemployment rate of 46% because of problems such as needing physical dependency, inability to drive or travel alone, lack of opportunities and psychiatric problems such as anxiety, depression and personality problems.14 In addition, Liou HH and colleagues15 compared the QOL between PWEs and patients with non-epileptic seizures and found that PWEs suffered from a much lower QOL, and that PWEs who are employed and married will have better QOL than PWEs who are unemployed and unmarried. Mrabet H16 and others compared the QOL of PWEs with a sample of 120 people from the general population using SF-36, which is used for assessing general QOL. It was found that PWEs had an average QOL lower than the general population in 3 areas; general health perception, mental health and social function, and found that factors affecting the health-related QOL of PWEs were the frequency of seizure, the time since the last seizure and side effects from antiepileptic drugs.

The main treatment for epilepsy is antiepileptic drugs (AEDs). The appropriate use of antiepileptic drugs results in the complete efficacy of medication and PWEs can return to a seizure-free status in a short time. In a case where the patient has not had an epileptic seizure for over 2-5 years, it may be possible to reduce or stop drug intake on a case by case basis.17 Patients who have had inappropriate treatment for a long time or do not respond to antiepileptic drugs therapy are being affected by drug-resistant epilepsy.18 Epilepsy surgery should be considered when at least two AEDs have failed to control the seizures, this is very expensive and can only be done in tertiary care hospitals.13

As mentioned above, epilepsy can be treated if diagnosis and appropriate treatment options are provided by a neurologist. Currently, there are many clinical practice guidelines for epilepsy, but they are not clear about epilepsy centers’ quality indicators. Fountain NB and the American Academy of Neurology Institute (AANI)19 developed quality indicators for caring for PWEs. They reviewed the evidence documents and guidelines from the period 1998 to 2008, which were refined to 8 candidate measures. In 2014, the AANI and the working team revised and defined new epilepsy measures called the Epilepsy Quality Measurement set (EQMs), where 7 key indicators are required to be used by all clinics.20 Consequently, the researchers at Bangkok Hospital Headquarters(BHQ) applied the EQMs to their assessment so that the patient’s care process can follow the high-quality standards that have been set by AANI and furthermore, to improve the quality of care for PWEs.

In Thailand, a previous analytic study of epileptic patients who underwent surgery and who did not undergo surgery at Chulalongkorn Hospital found surgery to be positively correlated with the QOL, while the duration of disease and depression had a negative correlation to QOL.21 Moreover, the QOL of epileptic out-patients at Srinagarind Hospital had a lower QOL on the general health perception, lesser vitality (energy/ fatigue) and mental health (depressive and anxiety symptoms) subdomains, respectively.22 However, most research into QOL in Thailand have been undertaken in government hospitals with limited population. Therefore, the researcher was interested in researching in a tertiary care private hospital, as this has not been done before. As well as that, the role of socioeconomic status is not clear, which can be further explored.

In addition, a team of experts developed the Thai version of the QOLIE-31-P23-25 for measuring QOL in PWEs. This was created in order to be consistent with changes in disease, and our researchers were able to use this questionnaire in this study. We expected the results to point out the benefits of using a specific screening tool for evaluating and improving the QOL of PWEs that allow them to maintain their normal daily life and activity.

The purpose of this cross-sectional descriptive study is to evaluate the clinical outcomes of care in the form of seizure frequency and QOL for PWEs. Another objective is to assess a patient’s care process and the epilepsy clinic compliance rates to the EQMs standard.20

This research was conducted in the epilepsy outpatient clinic at Bangkok Hospital Headquarters (BHQ), a private tertiary care hospital that enrolled subjects from July 2016 to December 2018. The subjects were purposively selected with the following inclusion criteria:

1. Thai patients who are over 18 years of age and diagnosed with epilepsy, and are currently being treated with antiepileptic drugs (AEDs) for at least 1 year and has never had epilepsy surgery.

2. Able to complete the Thai version of the QOLIE-31-P questionnaire and returned for the 12-week follow-up to the epilepsy clinic at BHQ. We excluded the PWEs who had unstable chronic diseases or had cognitive deficits that were examined and evaluated by their neurologists.

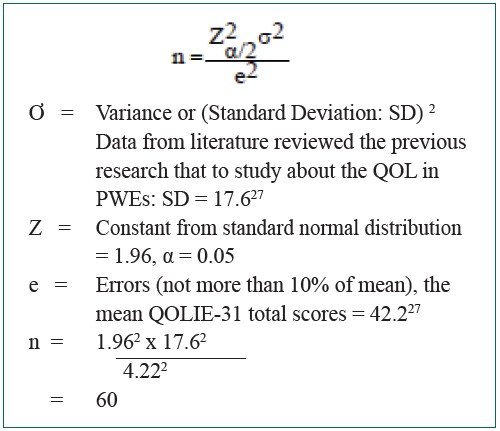

The sample size was calculated by reference to the previous similar study that had estimated the parameter based on the population proportion.26 We added an additional 10% to compensate for dropouts to avoid missing data. The minimum number of participants required for this study was 66, which was approved by a biostatistician according to the formula below:

Instruments

This study has instruments consisting of 2 questionnaires, namely

1. Case Record Form, divided into 2 parts:

Part 1: The demographics characteristics: This was created

from literature reviews that include demographics data (gender, age, education) and clinical characteristics of participants (age of first seizure, duration of epilepsy, etiology, seizure type, seizure frequency and side effects of AEDs.

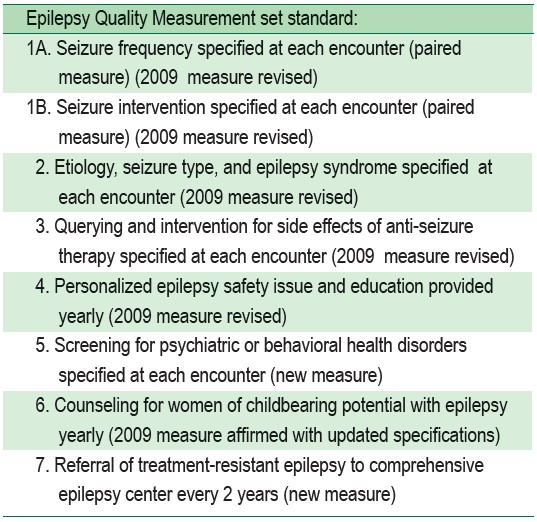

Part 2: The Epilepsy Quality Measurement set (EQMs)20: The purpose of this measurement is to present and explain what should be followed during the interaction with PWEs to ensure quality care is provided. The first set of epilepsy measures was developed by searching through evidence- based literature, finding 19 guidelines and 2 consensus papers by the co-chairs and facilitators such as American Academy of Neurology, American Epilepsy Society, Child Neurology Society, Epilepsy Foundation and American Academy of Neurology. The systematic assessment that were refined to the original 8 measurements was approved by AANI and the Physician Consortium for the Performance Improvement (PCPI) committees in 2010.19 Later in 2014, AANI and the working group, which includes physicians, nurses, patients, and caregiver’s representatives from professional associations, used a Modified Delphi to review all measurements and updated the final 7 epilepsy measures. The researchers assessed the patient’s care process compliance rates of the epilepsy clinic at BHQ following EQMs by reviewing the medical record of participants. (A details as in Table 1 below)

Table 1: 2014 Epilepsy Update Quality Measurement set 20

2. Patient weights Quality of Life in Epilepsy-Problems: QOLIE-31-P 25

The QOLIE-31-P questionnaire was specifically designed to survey health-related QOL for adults (18 years or older) which was created and modified from the original QOLIE-31 (version 1).23, 24 The original QOLIE-31 has been translated into the Thai version with the Cronbach’s Alpha coefficient of each subscale higher than the acceptable standard (0. 7), except for the Cognitive function, Medication effect and Social function.28 Cramer J and the QOLIE Development Group23-25 developed both versions of QOLIE-31, whom the researchers asked for permission and copyright before we applied to the volunteers. Cramer J provided and sent back the Thai version of QOLIE-31-P, which the researchers used in this study.

The QOLIE-31-P consists of 38 items about individual health and daily activities. There were 7 subscales, including emotional well-being, social functioning, energy/fatigue, cognitive functioning, seizure concerns, medication effects and overall QOL. This questionnaire added one new item into each subscale, asking about the level of their distress when they had any problems and worries that are related to the disease. The criteria for interpreting the scores are in accordance with the scoring manual for the QOLIE-31-P 29 and overall scores values range from 0 to 100, where higher scores reflect greater QOL.

Ethics consideration

Before the study began, this study was approved by the Hospital Director and the Institutional Review Board (IRB) of Bangkok Hospital Headquarters and Network Hospitals.

Data collection

The data of PWEs were selected using a simple random sampling method and collected from their medical records. First, the neurologists took a health history assessment, completed a physical examination. The epilepsy coordinator nurse screened the initial volunteers according to the inclusion criteria specified. After that, she invited volunteers who had qualified from their medical records and explained in detail the Participant Information Sheet (PIS) and participants were given the opportunity to ask questions about this study. Next, the volunteers agreed and signed consent forms to participate in this study through face-to-face interaction. Volunteers are allowed to refuse to take part in the study. Then, the participants take part in the self-assessment, where they were directly evaluating their status on the Thai version of QOLIE-31-P questionnaire by notifying when they visited an epilepsy clinic at the baseline visit and the follow-up at approximately 3 months ± 2 weeks. After that, the epilepsy coordinator nurse collected all documents to be sent back to the research nurse. Finally, the research nurse recorded the demographic data and specific information, including the patients care process epilepsy clinic compliance rates reviewed from medical records of participants which according to the Epilepsy Quality Measurement set 20 are put into the Case Record Form (CRF).

Statistical Analyses

Data analyses were conducted using the IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 22.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). The p-value was based on two-tailed tests with a significant level of less than 0.05 and using statistical methods as follows:

The demographic data and clinical characteristics data of participants were analyzed by using descriptive statistics with frequency distribution, such as percentage values, average values and Standard Deviations (SD)

Summary of the patients care process compliance rates by using a percentage

Analysis according to objectives:

3.1 Comparing the seizure frequency (baseline visit and 12-week follow-up) by using statistical Fisher’s Exact Test 3.2 Comparing the QOL of PWEs (baseline visit and 12-week follow-up) by using statistical paired T-test

The demographic characteristics of participants

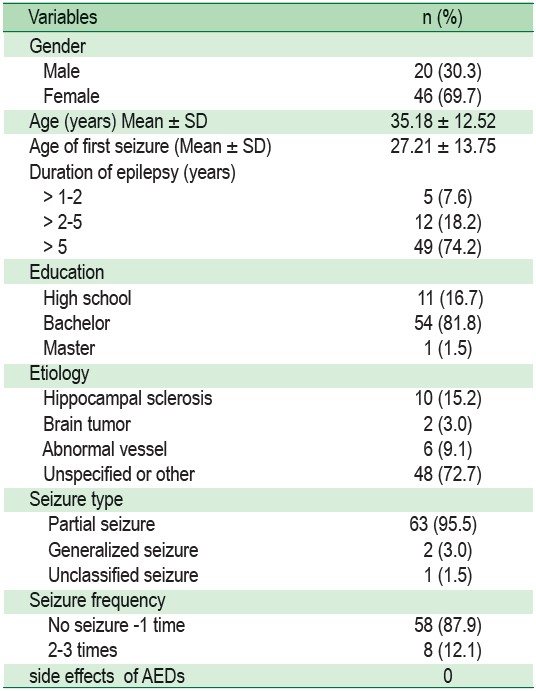

There was a total of 66 participants in this study. More than two-thirds of the participants were female (69.7%). The average age of participants was 35.18 ± 12.52 years (Min = 20, Max = 70), and the average age at the time of first seizure onset was 27.21 ± 13.75 years (Min = 5, Max = 65). Duration of epilepsy was found to be more than 5 years (74.2%). Most participants had a bachelor degree level of education (81.8%). Etiology of seizure was found in unspecified regions (72.7%), Hippocampal sclerosis (15.2%) and abnormal vessel (9.1%). The seizure type was divided into partial or focal seizure (95.5%) and generalized seizure (3.0%). Frequency of seizures in the baseline visit found that 58.9% had either not experienced a seizure attack or had experienced an attack at least once and 12.1% had experienced seizure attacks 2-3 times in the last 3 months. All participants did not suffer from any adverse effects of antiepileptic medications (Table 2).

Table 2: The demographic and clinical characteristics of participants (n = 66)

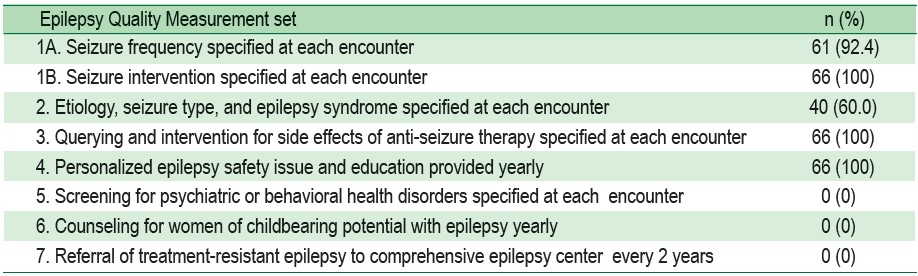

The patients care process compliance rates

The compliance rates of the epilepsy clinic at BHQ were reviewed with the medical records only once at baseline visit. The researchers found 100% of participants were documented about the seizure intervention, query and intervention for adverse effects of AEDs therapy and personal epilepsy safety issue and education. Almost all 61 (92.4%) of medical records documented the seizure frequency. More than 40 (60%) medical records noted the etiology, seizure type and epilepsy syndromes at each encounter, but not the screening for psychiatric or behavioral health disorders at each visit, the consulting for women of childbearing potential with epilepsy yearly and the referral of treatment-resistant epilepsy to comprehensive epilepsy center every 2 years have not been documented in their medical records (Table 3).

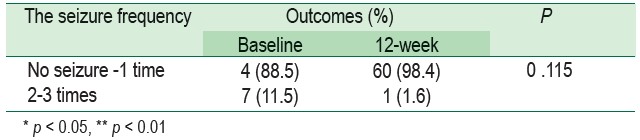

The comparison of the seizure frequency between baseline visit and 12-week follow-up of participants showed no sig- nificant differences in the seizure frequency observed after follow-up visit (p < 0.05), (Table 4).

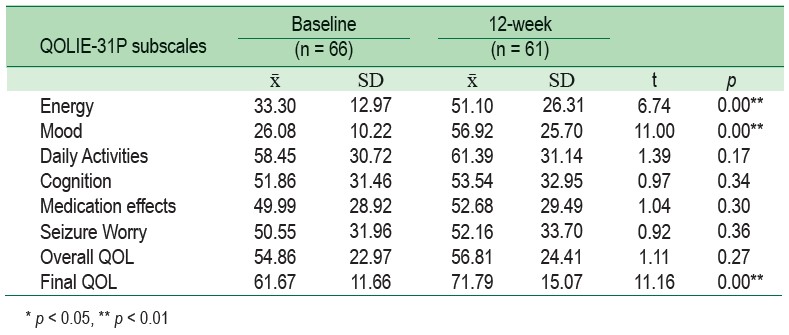

The final mean scores comparison of the QOL in PWEs at baseline visit (61.67 ± 11.66) were lower than 12-week (71.79 ± 15.07) follow-up in final QOL scores. This results detail at baseline visit, the highest mean score was for the Daily Activities (58.45 ± 30.72), while the lowest mean score was Mood (26.08 ± 10.22). At the 12-week follow-up visit found that the highest mean score was for the Daily Activities (61.39 ± 31.14), while the lowest mean score was for Energy (51.10 ± 26.31). Therefore, the comparison the QOL of PWEs between baseline visit and 12-week follow-up of participants found that there was a statistically significant difference in mood, energy subscales and final QOL scales (p < 0.01), (Table 5).

The findings presented in this study showed the patients care process compliance rates by the epilepsy clinic followed the EQMs standard, and it was found that 26 (40%) of reports did not document the etiology, seizure type and epilepsy syndrome at each visit. This finding was similar to a previous study in the US, where documentation of the etiology occurred in only 53% of the visits overall.30

This may be attributed to the fact that the etiology of seizure in this study were often unspecified (see in Table 2). Similarly, in a previous epidemiology study of epilepsy, the cause of the disease was still unknown in about 50% of global cases.31 The electroencephalography (EEG) or neuroimaging results may not clearly specify the etiology or seizure type. Neurologists may not have documented the record during every visit. Only 5 (7.6%) medical records did not document seizure frequency at each encounter, possibly because some records were described relative to the frequency of seizure as qualitative data (for example, “Same or better”) when the participants were clinically stable condition.

Table 3: The Epilepsy Quality measurement compliance rates (n = 66)

Table 4: Comparison the seizure frequency by using Fisher’s Exact Test (n = 61)

Table 5: Comparison the QOL scores by using the mean scores, SD and the Paired t-test

At each visit, screening for psychiatric or behavioral health disorders was not done because the neurologists may only document it when PWEs are suspected to have psychiatric symptoms or mental health problems. Upon suspecting the problem, physicians will record the condition and seek further consultation from a psychologist for a specific therapy depending on the health condition.32 Women of childbearing potential with epilepsy were advised for consultation with a specialist at least once a year. The doctors did not provide counseling for women of childbearing potential with yearly episodes of epilepsy, but offered only to the women with epilepsy who were planning to get pregnant. In the case of women with epilepsy who are pregnant, our clinical pharmacists advised about side effects, drug interactions and personalized safety issues at every visit whenever the patient was treated with AEDs in BHQ. The referral process for treatment-resistant epilepsy to comprehensive epilepsy center was not done every 2 years because the BHQ is a tertiary care hospital with advanced medical equipment services and was available for surgical therapy options for PWEs. BHQ is certified to an international standard, so patients do not need to be referred to other hospitals. Our results were consistent with the first report that adhered to the AAN epilepsy quality indicators, which reported their process for 200 PWEs at a tertiary epilepsy center in the US, and showed the measures resulted in lower compliance which may be caused by a different practice and a variety of documentation styles in medical reports.30 However, this quality measurement set alone may not improve patient care directly because it does not ensure high quality care but allows the assessment of the gaps in the care processes which can provide opportunities for quality improvement.33 This will help communicate with the healthcare system about the health status of PWEs, especially when the PWEs have unstable symptoms or emergency conditions. Documentation is an effective method for preventing misinformation and providing evidence in terms of clinical data which one or two of the measures may be selected to be used in each epilepsy clinic to implement the EQMs into practice.

Clinical outcome in this study was referred to as seizure frequency. In our participants, there were no significant differences in seizure frequency between baseline and follow- up at 12-week (p < 0.01). These findings were also found in a similar study in Israel.34 This was probably because the number of seizure frequency in this study was either no seizure attack or had experienced one seizure attack in the last 3 months (see Table 2), therefore our frequency numbers of seizure were not high. Our result was also similar to a previous study in the United Kingdom that from 1,652 PWEs, 51.7% had no seizure and 7.9% had one seizure in the last one year.35 These effects may be due to well-controlled seizures by physicians where seizure control was associated to affect seizure frequency.36 Epilepsy treatment goal is no seizure frequency and the maintenance of long-term seizure free with the least side effects.37 Our participants did not have adverse effects from

AEDs in 12-week (see Table 2). Likewise, a research conducted in Korea found 61.1% to be well-controlled epilepsy and that adverse drug reaction of AEDs and seizure control have complex interrelations that affect QOL of PWEs.38 Our results showed 72.7% unspecified etiology (see Table 2). If PWEs were unknown to the actual cause of seizure, they may not be able to change their behavior for avoid a specific stimulus of convulsions. Thus, the difference of seizure frequency may not be observed in this study. Consequently, physicians and nurses should increase specific knowledge about the triggers, aura and warning signs of seizure. Therefore, PWEs need the time to learn and practice self-observation, and nurse should be reassessing their knowledge and understanding consistently.39

In this study, the total mean scores of the QOLIE-31-P were compared between baseline and 12-week follow-up, and found the total mean scores of this questionnaire at baseline was lower than after 12 weeks. Our total mean scores result was higher than research in Russia40 but lower than a study conducted in Greece.41 When it was compared with the global QOLIE-31 scores, we found our mean scores result to be higher than the global mean scores.42 At baseline, our mood subscale showed the lowest scores, resembling the study in Estonia that also showed the lowest mean scores in role-emotional domain.43 At the follow-up visit, our results showed that the energy subscale had the lowest scores, similar to the studies in Australia44 and Iran,45 while the daily activities subscale showed the highest scores. Therefore, the difference in QOL scores may be different due to health conditions and demographic factors, such as gender,46 age,47 marital status48 and education level,49 cultures of the study volunteers27,35,38 or the use of different tools15,16,43 which may have caused the difference in their scores.

Our study showed statistically significant differences in mood, energy subscales and final QOL scores (p < 0.01). Our reports showed that the mean scores of the mood subscale were lowest at baseline visit and the energy subscale was the lowest at the 12-month follow-up (see Table 5). In accordance with most studies, the increase in seizures frequency resulted in a decrease in health-related QOL3,50,51 and reduced psychosocial function.44 In accordance with another previous study, anxiety and depression were found to be the most common psycho- logical co-morbidities of epilepsy,52 and had an impact on health-related quality of life in PWEs.53,54 Thus, patients may have felt anxious or depressed, resulting in unhealthy lifestyle choices such as lack of physical activity and feeling more fatigued.55 PWEs who had a more prolonged disease duration3 or have experienced poor seizure control related with depressive symptoms,55 may be suffering from a chronic mental health condition. Furthermo

re, another study found seizure frequency to be significantly correlated with seizure worries, emotional well-being and social functions subscales of the QOLIE-31 questionnaire.56 Therefore, if physicians can control or reduce the seizure frequency, they can improve the QOL of PWE. Likewise, uncontrolled seizures were found to significantly impact patient’s work, family and social life.35 Consequently, the health care provider should be aware of the importance of early detection by screening for changes in the patient’s QOL, including anxiety and depression, into routine practice. Physicians may advise for psychological support for patients with low QOL scores and signs of anxiety and depression in order to reduce psychiatric and behavioral health disorders and improve the QOL of PWEs.57

Epilepsy is a chronic disease that requires specialized care. PWEs may want to discuss with the nurses about their epilepsy care as a previous study in Australia found PWE and families wanting to actively participate in the management of their disease and how they wanted to be supported and care for.58 Self-management training program may be applied to patients in order to improve the QOL in PWEs as this program can help improve and maintain good QOL by teaching relevant knowledge and skills, and allow positive behavioral change.59

From the result above, an epilepsy nurse specialist can help an individual to ensure their understanding of the disease and self-care.60 Nurse specialist should clearly and accurately communicate health information to PWEs and families so they can cope better with the disease.61 For nurses who are not specialists in the epilepsy field, they may also use an Epilepsy Nursing Communication Tool (ENCT), a tool developed based on a literature reviewed by nurses in the American Association of Neuroscience Nursing and the American Epilepsy Society, which may help to improve communications and positive interactions between nurses and patients.62

Our study had some limitations. We conducted this study in a private hospital setting and some patients were transferred to the government hospital, meaning some participants were not able to do the 12-week follow-up, resulting in more time needed to complete the recording of the follow-up visits. This study has a small number of subjects for data analysis, therefore it may not be a representative of epilepsy in other settings. Our findings may also result from a random sample selection bias because most volunteers were healthy and stable condition with epilepsy. Therefore, further investigations should increase the number of sample size for more accurate results, as well as studying other sample populations, such as people with drug-resistant epilepsy or patient with epilepsy surgery.

The final QOL of patients at the Epilepsy Clinic at the BHQ had statistically significant differences between baseline and 12-week follow-up visit. The seizure frequency indicated no significant differences between baseline and 12-week follow-up. Seizure frequency may not be the only single factor that represents a valid index to completely evaluate the clinical outcomes. Psychological factors and other clinical factors as seizure severity, seizure-free duration may be involved, and its effect on QOL of PWEs. Healthcare providers should be aware of these factors while trying to improve patient-centered outcomes.

The researchers would like to thank Mr. Warut Chaiwong, Bangkok Health Research Center of Bangkok Dusit Medical Services for his suggestions in the statistics section.