Migraine is a common chronic neurological disorder characterized by recurrent episodes of disabling headaches. It is also known as one of the most debilitating disorders. Approximately 90% of migraineurs experience moderate to severe pain, and 75% have impaired function during migraine attacks and 53% reported severe impairment or require bed rest during their attacks.1,2 Approximately one third of migraineurs had missed at least one day of work or school in the last year and often have decreased productivity by at least one half.3-5 Hypersensitivity to light (photophobia), sound (phonophobia), smell (osmophobia), and head movement, along with nausea and vomiting are associated with the attack.6

The pathophysiology of migraine is still not fully understood but the vascular theory has been discarded. Central nervous system dysfunctions, including brain excitability and abnormality in pain modulating circuits in the brain stem, have been recently proposed as contributory factors.7,8 Functional neuroimaging studies of migraineurs suggest dynamic dysfunction between the periaqueductal gray matter (PAG) and several brain areas within nociceptive and somatosensory processing pathways. The impairment of the descending pain modulatory circuit causes loss of pain inhibition and hyperexcitability along both spinal and trigeminal nociceptive pathways, leading to a migraine attack.9,10

This review covers the pharmacological treatments of episodic migraine according to guidelines from the 2012 American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the American Headache Society (AHS) and the European Federation Neurology Society (EFNS). In addition, an emerging treatment in chronic migraine, Botulinum toxin type A, is reviewed.

Migraine was ranked the 12th most disabling medical disorder in women and the 19th in men by the World Health Organization (WHO) in 2005. With the publication of the World Health Report 2001 with evidence of the high burden of migraine, WHO recognized headache disorders as a high-priority public-health problem.11

Global prevalence of migraine was 10% and life-time prevalence for migraine was 14% according to a study by Stovner et al in 2007.12 The American Migraine Prevalence and Prevention (AMPP) study, the largest population based study of migraine, demonstrated a high prevalence of migraine in the general population. The prevalence estimate of unadjusted 1-year period migraine is 11.7%, with a higher prevalence among women than men (17.1% for women vs. 5.6% for men).

The prevalence of migraine was highest in those aged 30-39 years for both men (7.4%), and women (24.4%). This study also showed that migraine remained underrecognized and undertreated.1

Approximately 90% of migraineurs have moderate to severe pain, 75% have reduced ability to function during headache attacks, and 30% require bed rest during their attacks.13 Most migraineurs use only acute medication for their headaches. Approximately 40% of migraineurs are eligible for migraine prevention measures, but only 13% are currently receiving it.1,14-16

Preventive therapies can decrease the occurrence of migraine by 50-80%, reducing the severity and duration of migraine, and also improve acute medication responsive- ness.1,17 These therapies may help prevent the progression of episodic migraine to chronic migraine with a resulting reduction of health care cost.18,19 The quality of life of migraine patients is also improved.20

Preventive therapies can decrease the occurrence of migraine by 50-80%, reducing the severity and duration of migraine, and also improve acute medication responsive- ness.1,17 These therapies may help prevent the progression of episodic migraine to chronic migraine with a resulting reduction of health care cost.18,19 The quality of life of migraine patients is also improved.20

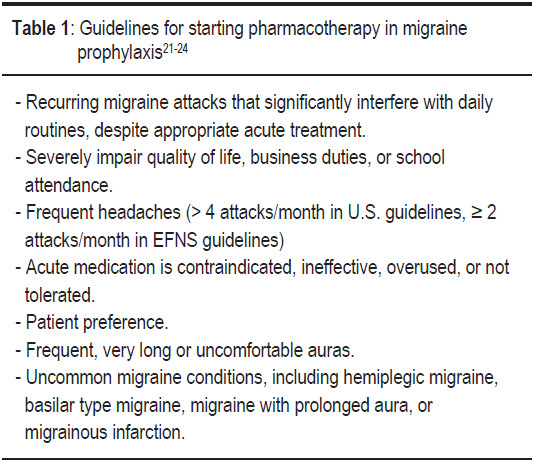

The United State (U.S.) evidence-based guidelines for migraine and EFNS guidelines on the drug treatment of migraine have established the circumstances that might warrant preventive treatment (Table 1).21-24

Guidelines suggest starting preventive medicines at a low dose and to increase the dosage slowly every 1-2 weeks or more until there is a therapeutic effect and to test the patient’s tolerance to side effects from the medications. An adequate trial duration of 2-6 months with an appropriate dosage is necessary to determine the efficacy of treatment. Efficacy is often first noted at 4 weeks. Medication over- use should be monitored regularly. Patients’ progress and symptoms should be monitored with a headache calendar or diary. Comorbid conditions such as depression, anxiety, epilepsy, cardiovascular disease, and obesity should be factored in. Women of child bearing age should be alerted to the side effects of medication during pregnancy. Once the headaches become under control for 6-12 months, the preventive medicines should be slowly tapered off.21-24

A longer period of preventive treatment (lasting more than 12 months) is suggested for patients who are at risk for migraine progression such as: high attack frequency (> 6 attacks/month), medication overuse (> 10 tablets/ month), obesity (BMI > 30), history of a head injury, snoring or experience of a stressful life event.25-31

The choice of preventive medication has to be carefully discussed with the patient. The efficacy of any agent, its potential side effects and experience of previous treatment trials, interaction with other drugs, and comorbidities should be considered for each individual patient. The updated 2012 guidelines from the American Academy of Neurology (AAN) and the American Headache Society (AHS) classify preventive agents on 4 levels based on published clinical trial evidence: Level A (established efficacy), Level B (probable efficacy), Level C (possible efficacy) and Level U (inadequate or conflicting data).32,33

Level A medications for episodic migraine prevention include antiepileptics (divalproex sodium/sodium valproate, topiramate), beta-blockers (metoprolol, propranolol, timolol), and herbal remedies (butterbur). The guidelines’ authors suggest that Level A drugs should be offered to patients who required prophylaxis for migraine.

Level B medications include several non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs - NSAIDs (naproxen/naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, fenoprofen), antidepressants (amitriptyline, venlafaxine), histamines (subcutaneous histamine), herbal remedies (feverfew), vitamins (riboflavin), and minerals (magnesium). Level B drugs should be considered for patients who require prophylaxis for migraine.

Level C medications include 11 drugs that may be considered for patients requiring migraine prophylaxis. Two antihypertensive medications (candesartan and lisinopril) are included in this class. NSAIDs (mefenamic acid, flurbiprofen), antihistamines (cyproheptadine), beta-blockers (nebivilol, pindolol), and minerals (co-enzyme Q-10) are also in this class.

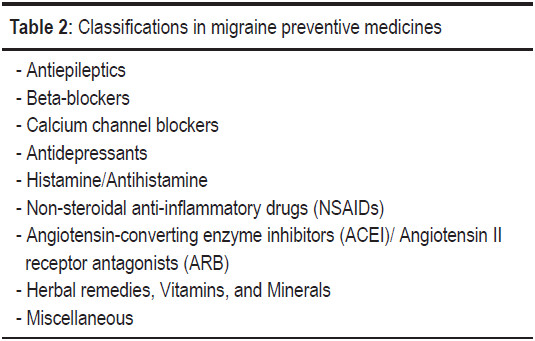

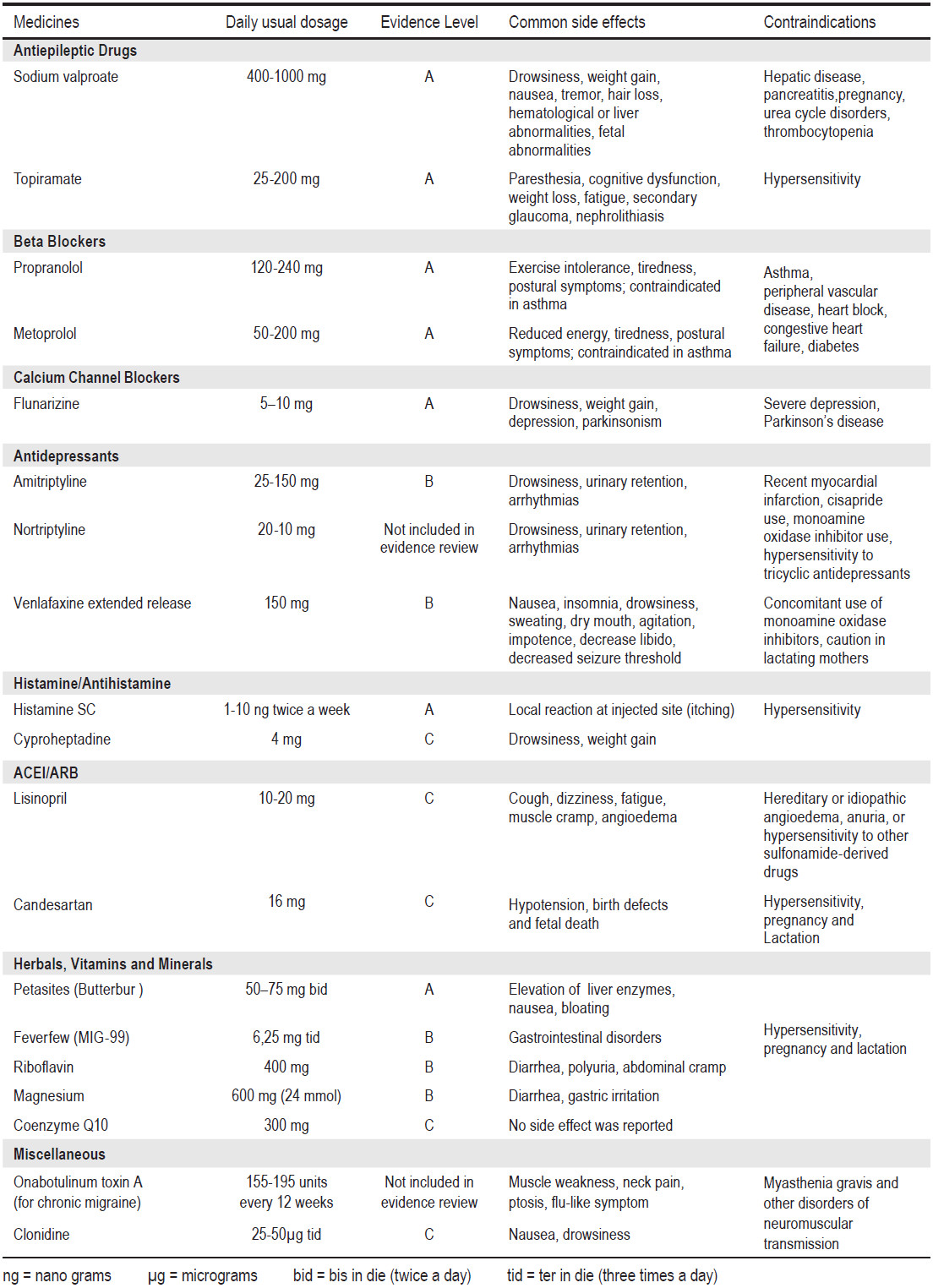

Classifications of medicines in migraine prevention are shown in Table 2. The recommended dosage and levels of evidence of efficacy of migraine preventive medicines are shown in Table 3.

Meta-analysis suggests that antiepileptics are an effective prophylaxis for migraine. Mean migraine frequency is significantly reduced by 1.3 attacks per 28 days compared with placebo (weapon of mass destruction (WMD) -1.31; -1.99, -0.63). Patients are 2.3 times more likely to have a ≥ 50% reduction in frequency with antiepileptics than with placebo (relative risk (RR) 2.25).34 Topiramate and sodium valproate are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (U.S. FDA) for prophylaxis with strong evidence of efficacy. The updated AHS/AAN 2012 guidelines also classify topira- mate and sodium valproate as level A medications.

Topiramate

Topiramate is a voltage-activated Ca2+ and Na+ channel blocker, it enhances gamma-aminobutyrate (GABA) at GABA-A receptors, it modulates the AMPA/kainate subtype of glutamate receptors, and it inhibits carbonic anhydrase (with selectivity for CA II and CA IV isoenzymes).35 Topiramate significantly inhibits trigeminovascular activity in the trigeminothalamic pathway via the kainate receptor.36

A dosage of between 100-200 milligrams per day (mg/d) has been shown to be superior to a placebo in the prevention of episodic, chronic, refractory, pediatric migraine, and migraine with medication overuse.34,37-39 Slow titration from 12.5mg to 25mg may improve tolerance. Common adverse effects are: paresthesia on extremities, weight loss, anorexia, taste interference, memory problems (slow cognitive processes and de- layed word retrieval), nausea, and fatigue. Patients with renal stones or a history of renal stone condi- tions should avoid this medication. Topiramate has re- cently been reclassified as a category D medication in pregnancy due to the risk of oral cleft lip/cleft palate abnormalities (RR 5.4; 95% CI = 1.5-20.1).40 The idiosyncratic syndrome of myopia with secondary glaucoma is a rare but potentially severe complication. Immediate discontinuation and emergency ophthalmic consultation can prevent permanent visual loss.41

Sodium valproate

Sodium valproate increases GABA levels in synapses,it increases potassium conductance and produces neuronal hyperpolarization, with an attenuation of low threshold T-type Ca2+ channels, a blocking of voltage-dependent Na+ channels and an attenuation of plasma extravasation.42 Valproate turns off the firing of serotonergic neurons (5-HT) of the dorsal raphe; this is implicated in headache control.

In clinical trials, the dosage varies from 500mg to 1,500mg/d. Begin with a dose of 250mg at bedtime and slowly increase to 1,000mg/d, although some patients may benefit from a dosage of up to 1,500mg/d. Valproate led to a significant reduction in migraine frequency and a 50% respondent rate which is significantly superior to the placebo. The most frequent adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, alopecia, tremors, weight gain, and dizziness.34,37,39,42

Valproate has also been associated with encepha- lopathy, an elevation of liver enzymes, pancreatitis and agranulocytosis. Before administering sodium valproate, special attention must be paid to hepatic, hematologic and bleeding abnormalities.

Baseline laboratory studies and follow up studies including valproate levels, liver enzymes (LFT), and complete blood count (CBC) are needed. Absolute contraindications to valproate are: pregnancy or the chance of falling pregnant, any history of pancreatitis, hepatic disorders, and hematologic disorders (thrombocy- topenia, pancytopenia, and bleeding disorders).43

Beta-blockers

Beta-blockers are a first-line drug in migraine prophylaxis. The main mechanism of beta-blockers in migraine prevention is considered to be mediated by the inhibition of central beta-1 receptors and consequently the inhibition of Na+ release and tyrosine hydroxylase activity. It also reduces the noradrenergic neuronal firing rate in locus coeruleus, it regulates the firing rate of PAG and it blocks 5-HT2C and 5-HT2B receptors.44

Clinical trials support the efficacy of propranolol (120-240mg/d), metoprolol (50-200mg/d), timolol (10-15mg bid), and atenolol (50-100mg/d). Propranolol is superior to a placebo in reducing migraine frequency by ≥ 50% (OR 1.94, 95% CI = 1.61-2.35, p < 0.00001).45

Table 3: The recommended dosage and levels of evidence of effi cacy of migraine preventive medicines.24,32,33

In a clinical study of propranolol, the dropout rate due to adverse effects was 5.3%.45 Common adverse effects are fatigue, exercise intolerance, drowsiness, insomnia, nightmares, nausea, dizziness and depression.

Metoprolol, propranolol, and timolol are all level A medications as recommended in the latest guidelines.32

Calcium channel blockers

Flunarizine, a non-specific calcium channel blocker, has show effectiveness in migraine prophylaxis in several studies.46,47 The mechanism in migraine prophylaxis could be due to the blocking of serotonin release and the attenuation of dural vasodilatation or probably by the blocking of L-type Ca2+ and Na+ channels and a reduction in NO synthesis.44 The dosage is 5-10mg/d, and female patients seem to benefit from a lower dose than males.48 Meta-analysis showed a significant reduction in the frequency of attacks with flunarizine 10mg vs a placebo (95% CI = 0.215-0.895; p = 0.002).49 Antiserotonergic effects such as sedation and weight gain are the most frequent side effects. Flunarizine should be avoided by the elderly due to a risk of extrapyramidal side effects (parkinsonism). Flunarizine is not approved for migraine prophylaxis in many countries including the U.S. However in EFNS guidelines, flunarizine was recommended as one of the first choice medications for migraine prophylaxis (level A).24

Verapamil, an L-type calcium channel blocker, is used in both migraine and cluster headache prevention. A dosage of between 120-180mg/d is commonly prescribed. Side effects include constipation, dizziness, hypotension, and cardiac conduction block. Verapamil was downgraded to a level U medication in the 2012 guidelines due to data conflict.

Antidepressants

Antidepressants have been commonly used in migraine and tension-type headache prevention. Amitriptyline, the tricyclic antidepressant (TCA), has had several small but non controlled studies. Amitriptyline blocks the neuronal uptake of both serotonin and norepinephrine, and also inhibits the activation of the trigeminovascular system.

TCAs are more effective than placebos in reducing migraine frequency (mean difference -0.7, 95% CI = -0.93 to -0.48) but are not superior to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs). Both TCAs and SSRIs reduce the intensity of migraine ≥ 50% than a placebo (OR 1.8, 95% CI = 1.24-2.62 for tricyclics and OR 1.72, 95% CI = 1.15-2.55 for SSRI).50 A recent large randomized control trial of amitriptyline, with a dosage of 25-100mg/d for 20 weeks, showed a statistically significant superiority of amitriptyline over a placebo in migraine prophylaxis at 8 weeks (25% vs. 5%, p = 0.031) and at 16 weeks (46% vs. 9%, p = 0.043) but not at 12 or 20 weeks.51 Common side effects are dry mucous membrane, somnolence, constipation, dizziness and urinary retention.

A dosage of between 25-150mg/d of amitriptyline and 100mg/d of nortriptyline showed benefits in migraine prevention. Some patients can tolerate and respond to a very low dose of 2.5-5mg/d. TCAs can be useful in patients with insomnia or fragmented sleep. On the other hand, prolonged sedation in the morning is a common adverse effect that can be improved by adminis- tering the medication in the early evening.

Extended release Venlafaxine, is a selective serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (SNRI). The dosage of 150mg/d for 2 months showed a statistically significant reduction in the number of headache attacks compared to a placebo (p = 0.006) throughout the treatment period. Patient satisfaction was significantly different in the active group when compared to the placebo group (p = 0.001 at visit 2 and visit 6). The treatment benefits were rated good or very good in 80% of patients in the 75mg group and 88.2% of the patients in the 150mg group.52 Adverse effects include nausea, vomiting, insomnia, nervousness, and decreased seizure threshold.

Histamine/Antihistamine

Histamine

Histamine showed efficacy in migraine prevention in three class II studies.53-55 N-alpha-methyl histamine, 1-10 nano grams (ng) subcutaneous injection (SC) twice a week reduced headache frequency from 3.8 at baseline to 0.5 in the histamine group at 4 weeks of treatment (p < 0.0001). Histamine was superior to the placebo in the reduction of migraine frequency, severity and duration through 12 weeks of treatment (p < 0.0001). The reported adverse side effect of histamine SC was only a short lived itchiness at the injection site.53

The second study showed an equivalent efficacy of a 500mg daily sodium valproate dosage when compared to a 1-10ng for 2 times/week histamine SC injection. Headache frequency, duration, and intensity improved after only 8 weeks of treatment (p < 0.05). No adverse side effect was reported in the histamine group. Conversely, the sodium valproate group reported nausea 37%, tremors 34%, weight gain 24% and alopecia 12%.54

The third study of topiramate (100mg/d) was compared to a dosage of histamine 1-10ng for 2 times/ week SC. Both active groups showed improvement over the baseline in attack frequency, intensity, and the use of rescue medication. Eleven percent of the histamine group withdrew from treatment due to a lack of satisfaction with the speed of results.55

Antihistamine

Cyproheptadine, the antagonist of the histamine H1 receptor, 5-HT2, L-type calcium channel and muscarinic cholinergic receptor, is commonly used in childhood migraine prophylaxis. Cyproheptadine (4mg/d) was as effective as propranolol (80mg/d) in reducing migraine frequency and severity. A combination of cyproheptadine and propranolol was more effective than monotherapy.56 Common side effects reported include drowsiness, weight gain, dry mouth, nausea, diarrhoea, and ankle oedema.

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs)

Some NSAIDs including naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, ketoprofen and fenoprofen have modest but significant migraine prophylaxis properties.33,57 However, the regular use of NSAIDs for migraine prevention may exacerbate medication overuse, headache, and other adverse side effects including gastrointestinal disturbances, renal toxicity and increased cardiovascular risk. NSAIDs are more suitable for short term prophylaxis such as in menstrual-related migraine.

Aspirin (ASA) has been used in migraine prevention, but its efficacy remains controversial. A study comparing 300mg of ASA to 200mg of metoprolol in migraine patients showed metoprolol was more effective than aspirin (respondent rate 56.9% vs. 42.7%).58 In another study, ASA 100mg given in combination with vitamin E 600 IU compared with a placebo in combination with vitamin E showed no difference in migraine frequency or severity of migraine at 12 months and 36 months.59

In the updated 2012 guidelines naproxen/naproxen sodium, ibuprofen, ketoprofen, and fenoprofen are classified as level B medications. Mefenamic acid and flubiprofen are classified as level C medications.

Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitors (ACEI) and Angiotensin II receptor antagonists (ARB)

Lisinopril (10mg twice a day (bid)) and candesartan (16mg/d) showed prophylaxis properties in migraine patients. They have been graded as level C medications as per recommendations in the latest updated AHS/AAN guidelines.

The mechanism of ACEI and ARB for migraine prophylaxis might be an attenuation of the central sympathetic tone, inhibition of oxidative stress, promotion of degradation of pro-inflammatory factors such as substance P, encephalin, and bradykinin and probably modulation of endogenous opioid systems.44

Lisinopril

Lisinopril, an angiotensin converting enzyme inhibitor (ACEI), was studied in a double-blind placebo-controlled test as a migraine prophylaxis. The treatment period was 12 weeks with 10mg/d lisinopril for 1 week then 10mg twice daily for 11 weeks, followed by 2 weeks wash-out period compared to a placebo. Headache hours, headache days, migraine days, and the headache severity index were significantly reduced by 20% (95% CI = 5-36%), 17% (95% CI = 5-30%), 21% (95% CI = 9-34%), and 20% (95% CI = 3-37%) respectively in the lisinopril group. Adverse effects include: arterial hypotension, a dry cough, and fatigue.60

Candesartan

Candesartan, an angiotensin II receptor antagonist (ARB), showed efficacy in reducing headache days in a randomized, double-blind, placebo controlled, cross-over study of candesartan (16mg/d) over 20 weeks (4 weeks of run-in period, 12 weeks of treatment, and 4 weeks of washout). During the 12 weeks treatment period, the mean number of days with headaches was statistically reduced (13.6 vs. 18.5 days, p < 0.001). The number of candesartan respondents (reduction of 50% compared to the placebo) was 31.6% for days with headache, and 40.4% for days with migraine. The tolerability profile of candesartan was comparable with the placebo.61

Herbal remedies, Vitamins, and Minerals

Petasites

Petasites (butterbur) is a purified extract from the Petasites hybridus root. Two studies by Grossman et al.62 in 2001 and by Lipton et al.63 in 2004 showed Petasites (50-75mg bid) was effective in reducing migraine attack frequency. In the first study, the frequency of migraine attacks decreased by a maximum of 60% versus the baseline and a significant reduction in the number of migraine attacks compared with the placebo (p ≤ 0.05). In the second study, over a 4 months treatment period, migraine attack frequency was reduced by 26% in the placebo, and by 48% with Petasites extract (75mg bid) (p = 0.0012 vs. placebo), and 36% in Petasites 50mg bid (p = 0.127 vs. placebo). The most frequent adverse effects were: mild gastrointestinal events, predominantly burping. The currently updated guidelines considered butterbur effective (Level A) for the prevention of episodic migraine headaches in adults.32,33

MIG-99 (Feverfew)

MIG-99 is extracted from tanacetum parthenium (feverfew). Two studies by Pfaffenrath et al.64 in 2002 and Diener et al.65 in 2005 showed the benefit of MIG-99 in migraine prophylaxis. In the first study (class I study), migraine frequency decreased from 4.76 by 1.9 attacks per month in the MIG-99 group and by 1.3 attacks in the placebo group (p =0.0456). A logistic regression analysis of respondent rate showed an odd ratio of 3.4 in favor of MIG-99 (p = 0.0049). Adverse events were similar to the placebo, and the most common symptoms are gastrointestinal and respiratory system disorders.64

The second study (class II study), confirmed the efficacy of MIG-99 (6.25mg three times a day (tid)) in reducing the mean number of migraine attacks versus the placebo (1.8 vs. 0.3 attacks/month, p = 0.02, 95% CI = 1.07-2.49).65

Riboflavin (vitamin B2)

Mitochondrial dysfunction resulting in impaired oxygen metabolism may play a role in migraine pathogenesis.66 Riboflavin is the precursor of flavin mononucleotide and flavin adenine dinucleotide, which are required for the electron transport chain. Riboflavin improved abnormalities in mitochondrial encephalomyopathies and this has been studied in migraine prophylaxis.67-69

A high dose of vitamin B2 (400mg) was significantly superior to the placebo in reducing the attack frequency (p = 0.005), headache days (p = 0.012), and migraine index (p = 0.012). The number needed to treat (NNT) was 2.3. Adverse effects are transient mild diarrhea and polyuria.70

Magnesium

A prospective study of oral magnesium (trimagnesium dicitrate) (600mg (24mmol) or a placebo daily for 12 weeks in migraine patients showed that the attack frequency was reduced by 41.6% in the magnesium group and by 15.8% in the placebo group at week 9-12 compared to the baseline (p < 0.05). Migraine days and symptomatic drug use also decreased significantly in the magnesium group. Adverse effects were diarrhea (18.6%) and gastric irritation (4.7%).71

A combination of magnesium (300mg), riboflavin (400mg), and MIG-99 (100mg) was studied compared with the placebo (25mg of riboflavin). Both treatment groups showed improvement over the baseline, but no between-group differences were noted (42% respondents in the treatment group versus 44% in the placebo group; p = 0.87).72

Coenzyme Q10 (water-soluble disbursable form of Co-Q10)

Coenzyme Q10 is a mitochondrial cofactor involved in energy generation. Deficiency of coenzyme Q10 was found in 33% of childhood migraines.73 In an open label study, 61.3% of patients who received coenzyme Q10 (150mg/d) had a greater than 50% reduction in number of days with migraine. No side effect was noted.74 A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of coenzyme Q10 (100mg tid) for 4 months showed that the 50% responder rate was 47.6% compared with 14.3% by placebo (p = 0.02) (number-needed-to-treat = 3). The side effects reported were insomnia and dyspepsia.75

Miscellaneous Prophylaxis Drugs

Botulinum toxin type A

Botulinum toxin type A (BTA) inhibits acetylcholine release at motor nerve terminals.76 Experimental studies in rats showed anti-nociceptive properties.77,78 BTA is approved by the U.S. FDA for chronic migraine, defined as 15 or more headaches per month for at least 3 consecutive months, with clinical features of migraine without aura for at least 8 of those 15 days.79 Two phase 3 studies of BTA in chronic migraine have been completed: The Phase III Research Evaluating Migraine Prophylaxis Therapy with BTA 155-195 units (U) every 12 weeks with a 24-week, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled phase followed by a 32-week, open-label phase (PREEMPT 1 and PREEMPT 2).80,81

In the PREEMPT 1 study, the primary end point (change in number of headache episodes from the baseline) was similar in BTA and placebo groups (-5.2 vs. -5.3 episodes; p = 0.344), however the secondary endpoints are significantly different between the two groups, there is significant reduction in headache days (p = 0.006) and migraine days (p = 0.002) with the BTA group.80

The PREEMPT 2 study was reported to have achieved both primary and secondary endpoints. BTA was statistically significantly superior to the placebo for reducing the frequency of headache days per 28 days relative to the baseline (-9.0 vs. -6.7 days; p < 0.001).81

The pooled results from PREEMPT 1 and PREEMPT 2 also showed a statistically significant benefit of BTA over the placebo in reducing the frequency of headache days at 24 weeks (-8.4 vs. -6.6; p < 0.001). Adverse events were mild to moderate in severity and only a few patients discontinued (BTA 3.8%, placebo 1.2%) due to adverse effects.82

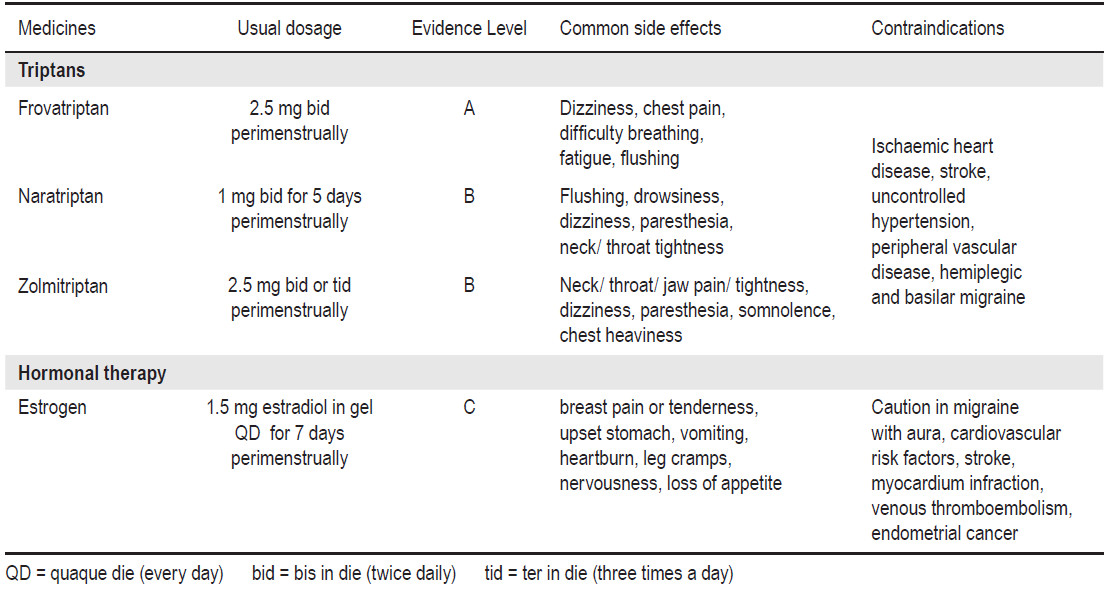

Table 4: Drug Recommended for Short-Term Prevention of Migraine Associated With Menstruation

Pooled analyses of the 56 weeks PREEMPT clinical trials showed that BTA was statistically significant in reducing the frequency of headache days in patients with chronic migraine at week 56 when compared to the placebo (-11.7 vs. -10.8; p = 0.019). Several secondary efficacy variables at week 56 were also statistically significantly reduced in the BTA group, including frequencies of migraine (-11.2 vs. -10.3; p = 0.018) and moderate/severe headache days (-10.7 vs. -9.9; p = 0.027) and cumulative headache hours on headache days (-169.1 vs. -145.7; p = 0.018). BTA was safe and well tolerated, with few treatments related to adverse effects.83 BTA is also effective in the subgroup of patients with medication overuse.84

α-adrenergic agonists

The centrally acting α2-adrenergic agonists clonidine and guanfacine have been used in migraine prophylaxis. Clonidine inhibits the firing of locus coeruleus neurons induced by activating presynaptic inhibitory α2 receptors. Clinical trials showed variable evidence and very few benefits.85,86 Clonidine and guanfacine have been classified as level C agents in the latest updated guidelines.32

Short-term prophylaxis may be useful in migraine associated with menstruation. Menstrual migraine is defined as attacks occuring during the 5 day interval of time extending from 2 days before through 3 days after the onset of menses.3 Drugs that have been used include NSAIDs, triptans, estrogen, magnesium, and ergot.87

Naproxen sodium (550mg oral bid) was the most commonly used NSAIDs for short-term prevention.88 However, NSAIDs are not mentioned in the latest updated guidelines.

Triptans seem effectivce in the abortive management of menstrual migraines.89 Systematic review of short-term prevention in perimenstrual migraine suggests frovatriptan (2.5mg bid) for 6 days perimenstrually (level A), naratriptan (1 mg bid) for 5 days starting 2 days before the expected onset of menses (level B), and transcutaneous estrogen 1.5 mg QD for 7 days (level C).90 The AHS/AAN migraine prevention guidelines for short-term prevention of migraine associated with menstruation is shown in Table 4.

Migraine is a chronic debilitating disorder that affects the patients’ quality of life. Migraine prevention should be considered for patients with frequent disabling migraine attacks (≥2 attacks/month), not controlled by acute medication, and complicated migraines. Preventive therapies include medication, behavioral, and alternative treatments. Topiramate, sodium valproate, metoprolol, propranolol, timolol, and butterbur are recommended as effective prophylaxis level A medications. Treatments and side effects of the treatments have to be discussed. Comorbidity should be considered and treated together.

Migraineurs need to have realistic expectations of success and be aware of the time needed for medication to take effect and the proposed duration of treatment. The goal of preventive therapy is to reduce the frequency, duration, and severity of migraine attack, to reduce disability, to improve patient functioning and to improve the responsiveness of acute attack medications in the future. Education is an important part of any successful treatment.

Patients need to be informed about the nature of the disease, its progression, the need for changes in lifestyle including the avoidance of known triggers, getting regular sleep, eating regular meals, and effective stress management. Non-pharmacologic interventions such as biofeedback, relaxation training, aerobic exercise, rehabilitation, and acupuncture can be considered for migraine patients.