Health care cost in Thailand was rising at a rate of 6.6% per year between the year 1995 and 2005.1 Cost containment is an important issue for all healthcare system, especially secondary and tertiary hospital.2-4 Therefore, hospitals have focused more on the limitation of hospitalization and strategies on reducing length of stay.5-8 In response to shorter lengths of stay, hospitals have identified discharge planning, which refers to all the health care arrangements made for and provided to the patient after discharge, as the important policy in combating high health care cost. It expects to increase readiness for hospital discharge and decrease the length of hospital stay, rate of emergency visits and readmission rate.9-15

For neurosurgical patients, factors influencing length of hospital stay (LOS) are both numerous and varied. Home healthcare nurses are primarily concerned with the transition from hospital to home and the effects of early discharge planning for these patients. They are worried that certain methods of care, including nasogastric feeding, suction, or respiratory care, are not properly understood before discharge. The readiness of caregivers on allowing patients to be discharged from hospitals may not be sufficient, leading to a delayed hospital discharge.

In Ramathibodi hospital, discharge planning is also a policy for every ward. At neurosurgical wards, nurses in the wards provide discharge planning for the patients. If the patients need special nursing care at home after discharge, the ward nurses refer the patients directly to home healthcare nurses. The home healthcare nurses provide discharge education to caregivers before the planned day of discharge. The contents of discharge education focused on daily care activities and specialized nursing care, such as nasogastric feeding, suction, or respiratory care. However, with a short period of time for discharge planning for home healthcare nurses, consequently, the information and skill on caring for the patients might be incomplete, and caregivers felt a low self-efficacy on caring for the patients, resulting in delayed hospital discharge. Therefore, a proactive discharge planning project was developed to improve the discharge planning process. The purpose of the project was to determine the effectiveness of proactive discharge planning by home healthcare nurses on caregiver’s perceived readiness for discharge and occurrence in delayed hospital discharge.

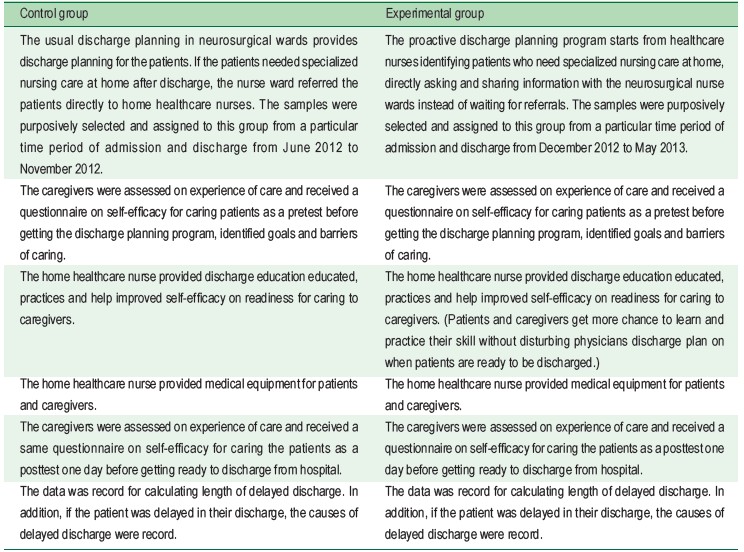

The study was a quasi-experimental study conducted from June 2012 to May 2013. It was part of a continuous quality improvement project which aims to improve the discharge plan process for the home healthcare unit. Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Review Board of Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University (ID 12-2014-23 Y). Prior to the beginning of the study, a request for administrative assistance was communicated to the head nurses of the surgical unit. Formal written consent was obtained from each participant before data collection.

Populations and samples

Caregivers were assigned to adult neurosurgical patients admitted in surgical wards at Ramathibodi hospital. The samples were purposively selected and assigned to the control group or experimental groups in a particular period of discharge planning. The 33 caregivers of adult neurosurgical patients who were admitted and discharged from June 2012 to November 2012 were assigned into the control group while the 33 caregivers of the patients who were admitted and discharged from December 2012 to May 2013 were assigned into the experimental group. Participants were eligible for this study if they met the following inclusion criteria:

Exclusion criteria were samples dead between studying.

The intervention

Instruments

The study instruments for data collection are as follows:

Basic data on patients included age, gender, educational level, length of stay and ADL score.15,16 Basic data on caregivers included age, gender, educational level, perceived health, secondary caregiver and relationship with patient.

The readiness for hospital discharge questionnaires are similar between pre-test and post-test questionnaires developed by Nichathima Srijamnong 2010,17 which has a reliability of 0.92. The scale was a 19-item scale, which was used to measure the caregiver’s confidence in caring for the patients. Each item was responded to Likert scale, 1-5 points (1 = Strongly Disagree, 2 = Disagree, 3 = Neutral, 4 = Agree, 5 = Strongly Agree); higher scores indicated higher level of maternal confidence. In this study, the internal consistency reliability was 0.93.

The discharge record sheet about admission date, planned discharge date ordered by a physician, actual discharge date and causes of delay discharge.

Statistical analysis

The statistical analysis was performed using Predictive Analytics Soft Ware (PASW) 18 program (Mahidol license). The number, percentage, mean and standard deviation of demographic data were calculated. A Chi-square test was used to analyze the categorical data and Mann-Whitney U test was utilized to analyze the continuous data to test the differences between the control groups and experimental group.

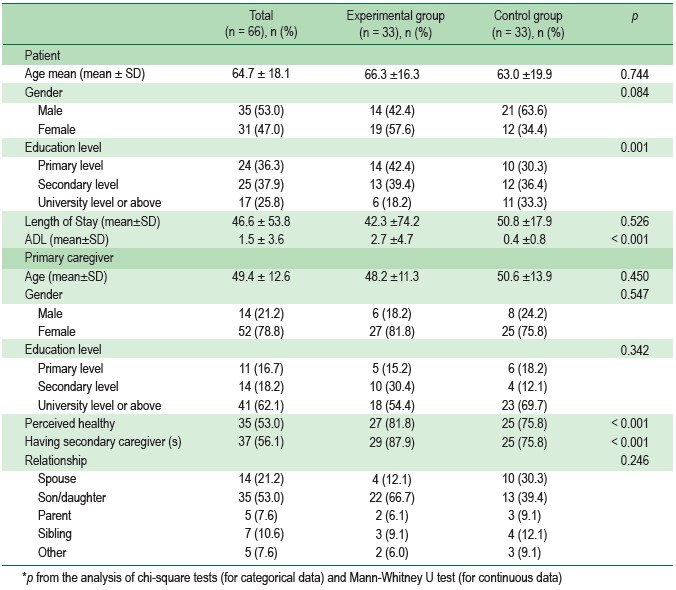

A total of 66 neurosurgical patients were recruited into control groups (33 patients) and experimental group (33 patients). The mean age was 64.7 ± 18.1 years. There were thirty-five male patients (53.0%) and 31 female patients (47.0%). Educational level of most patients was secondary level (37.9%). The mean length of hospital stay was 46.6 ± 53.8) days.

The mean age of the caregivers was 49.4 ± 12.6 years. Most caregivers were 52 female (78.8%), had completed Bachelor’s degree or above 62.1%. Most of them perceived themselves as healthy (53.0%). 37 caregivers (56.1%) have second caregivers helping them caring the patients. Half of the caregivers (53.3%) were son or daughter.

As shown in Table 1, there were no significant differences between control groups and experimental groups in basic data for patients and primary caregivers. This indicated that both groups were homogenous before the discharge planning program.

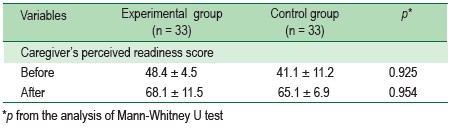

Readiness for hospital discharge

At the beginning of usual discharge planning for control group and proactive discharge planning program for experimental group, the perceived self-efficacy mean score of the caregivers in the control group was 41.1 ±11.2 and the experimental group was 48.4 ± 4.5. At the date before patients discharge from hospital, the perceived self-efficacy mean score of the caregivers in the control group was 65.1 ± 6.9 and the experimental group was 68.1 ± 11.5. Using Mann-Whitney U-test, there was no statistical difference between 2 groups at the beginning and at the discharge date.

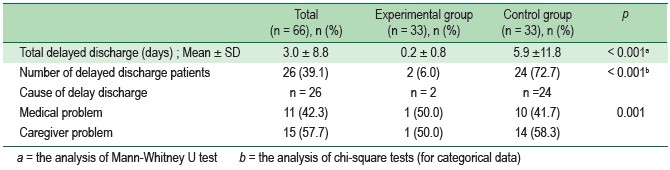

Length of delayed discharge

Length of delayed discharge days was significantly different between the control and the experimental group, with the mean being 5.9 ± 11.8 and 0.2 ± 0.8 respectively (Mann-Whitney U-test p < 0.001). The proportion of patients with delayed discharge was significantly different in the control and experimental groups (p < 0.001).

Causes of delayed discharge

Delayed discharge caused by medical problems and caregivers problems was significantly different in the control and experimental groups (p = 0.001).

The major results from proactive discharge planning program showed a shorter length of delayed discharge days than normal (the difference between experimental and control group was significant). However, in terms of sociodemo- graphic factors, these are higher in the experimental group:

It is possible that it is the result of increased readiness to discharge after the proactive discharge planning program. The result was similar to the studied of Uma Jantawises and et al.18 in stroke patients in Songklanakagarind hospital, Southern Thailand, which saw the decrease in length of delayed discharge from 7 to 6 days after using the clinical pathway implementation for discharge planning program. This was also similar to the study of Line Kildal Bragstad and et al.19 where patients with caregivers were found to be significantly associated with success and have a higher score of ADL than those without a caregiver who have low ADL score. The analysis of caregiver’s perceived readiness score revealed that despite an increase in caregiver’s self-efficacy after the program, the score was not statistically different between the two groups. Because home healthcare nurse provided discharge educated, practiced and improved self-efficacy on readiness for caring to caregivers of both groups, all caregivers, including those assigned to the control groups, received substantial levels of experience and confidence in a short period of time to take good care of patients before their discharge.

Table 1 : Basic data of patients and caregivers (n = 66)

Table 2 : Caregiver’s confidence of the experimental and control groups at before and after the intervention

Table 3 : Length of delayed discharge, number of delayed discharge patients and cause of delayed discharge of the experimental and control groups at before and after the intervention

The proactive discharge planning program was showed to be independent to home healthcare nurse’s role for better management of care. Patients and caregivers got more opportunities to learned and practiced their skills, especially caregivers in the experimental group. Therefore, home healthcare nurse and nurse ward should make discharge plans as soon as possible. The result was similar to the studied of Hager20 which revealed early discharge planning increased the patient readiness for discharge in both groups. The proactive discharge planning program could potentially improve discharge plan because home healthcare nurse can focus more on their routine jobs and improve hospital policy, therefore saving costs for both patients and hospitals. Home healthcare nurses and nurse ward should collaborate at an early stage to identify patients who need homecare without waiting for a referral from the nurse ward. The proactive discharge planning can create an opportunity for discussion between medical personnel, patients and caregivers that can reduce barriers and also fulfill gaps in transitional care.21

A limitation of this study was that the ADL score or other factors affecting the length of delayed discharge between the two groups were not compared and analyzed. Future investigations are needed to examine these issues and potentially bring a better understanding of the impact of proactive discharge planning.

In summary, the proactive discharge planning in neurosurgical patients is the pilot project for improving efficiency in the discharge planning program in order to avoid prolonged hospital stay and decrease length of delayed discharge in patients. This study proves the proactive discharge planning is an effective way to solve a problem of delay discharge patients from hospitals. More importantly, home healthcare nurses should apply proactive discharge planning and also provide it in other groups of patients who need continuing care to enhance the best outcome of caring.

This study was funded by Faculty of Medicine Ramathibodi Hospital, Mahidol University.